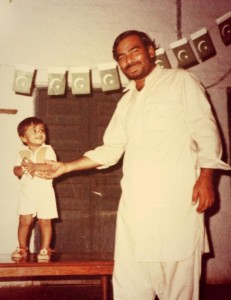

It was August 14, 1984. I was only two-years-old. My father decorated the veranda of our small house with lights and green buntings. My parents were excited, as were my elder brother and I. Though I was too young to remember, pictures of that day bring on a strong sensation of déjà vu.

Yet, and sadly, before the following Independence Day, we had to leave Pakistan. Persecution, which gained momentum under President Ziaul Haq, forced many Ahmadis to leave for safer lands. Many Ahmadis were killed and their businesses looted. The state, unfortunately, abetted the religious extremists by promulgating the notorious anti-Ahmadi laws, and arrested scores of Ahmadis nationwide for ‘crimes’ such as reciting the Kalima (Islamic Creed) or reading the Holy Quran. Among the scores arrested for their faith, three were my maternal uncles.

Therefore, I spent my formative years in a small peaceful country in West Africa. Even there, August 14 remained an important part of our lives. My mother – despite her brothers’ ordeal – played patriotic songs and related stories of our founding fathers, particularly of Mr Jinnah and Mr Zafarullah Khan. The latter is, unfortunately, a forgotten hero in the very land he fought alongside Jinnah to create. It is hard to conceive how the man who drafted the Pakistan Resolution, represented the state at the United Nations as Pakistan’s first foreign minister, and is the only Pakistani to have presided over both the UN General Assembly and the International Court of Justice, is conveniently denied any significant mention in our Pakistan studies text books.

Therefore, I spent my formative years in a small peaceful country in West Africa. Even there, August 14 remained an important part of our lives. My mother – despite her brothers’ ordeal – played patriotic songs and related stories of our founding fathers, particularly of Mr Jinnah and Mr Zafarullah Khan. The latter is, unfortunately, a forgotten hero in the very land he fought alongside Jinnah to create. It is hard to conceive how the man who drafted the Pakistan Resolution, represented the state at the United Nations as Pakistan’s first foreign minister, and is the only Pakistani to have presided over both the UN General Assembly and the International Court of Justice, is conveniently denied any significant mention in our Pakistan studies text books.

While growing up, I also learned about numerous other Pakistani Ahmadi heroes, including Dr Abdus Salam, General Iftikhar Janjua, Mirza Muzaffar Ahmad, General Akhtar Malik and General Abdul Ali Malik etc. I was always proud of the role my community played in creating, stabilising and strengthening Pakistan.

Then, when I was a young teenager, we decided to return to the motherland.

Even though I knew our freedoms were severely curtailed here, Pakistan was still the only place we called home. I remember watching cricket matches with friends and family, getting heartbroken when Pakistan lost, and cheering every six that flew off Shahid Afridi’s bat. I enjoyed Pakistani television serials, fell in love with Lahore, and felt a deep sense of duty to my land of birth. Every Independence Day my elder brother and I decorated our house in Rabwah with a flag and buntings – much the same way my father would when I was a kid.

But with every passing year, the horrid state of persecution and violence increased. Extremist clerics continued to engage in vitriolic hate speech, with no public figure ready to take the risk to condemn the persecution of the Ahmadis, let alone speak for their rights. The media and public were not interested in our cause either.

Then, a series of specifically targeted attacks on Ahmadi physicians made me finally rethink my future plans, and I moved to America. Having been here for almost seven years, I still proudly identify as a Pakistani American. The word Pakistan continues to be an integral part of my identity – and it always will be.

It is August 14 again today. And as much as I am excited, I sense a strange longing deep down in my heart. When will I be able to return to Pakistan as a free citizen of the state? When will Pakistan return to the path that Jinnah set it on?

We know well that Jinnah’s struggle for Pakistan was aimed at restoring equal rights and representation, and eradicating the pain of social discrimination and economic deprivation felt by a minority – the Muslims in United India. How did it happen then that the same country that was established to protect the rights of one minority now has stringent laws denying them to another?

And despite all of this, what an exemplary display of loyalty that Pakistan’s Ahmadis consistently speak of coexistence, not separation. They continue to seek tolerance, not division. They continue to be goodwill ambassadors for the country they helped found. You might see them criticise policies that are counter to Jinnah’s vision of the country, but you won’t ever see them hating Pakistan.

Why? Because Pakistan is our mother too. And how do you hate your own mother, even when she treats you bad?

So while I am celebrating my mother’s birthday with enthusiasm as usual, true elation will be the day my mother smiles back at me. I am longing for that day. It will be the day when you, my brothers, stand up to accept me as your equal under law. It will be the day when I will be able to go back home without the fear of being arrested or attacked for reading the Holy Quran, saying my prayer or identifying as I chose to. It will be the day when the discriminatory second amendment and anti-Ahmadi laws will cease to exist, except only as a dark chapter in books of history.

Happy Birthday Mother! Pakistan Zindabad!

Yet, and sadly, before the following Independence Day, we had to leave Pakistan. Persecution, which gained momentum under President Ziaul Haq, forced many Ahmadis to leave for safer lands. Many Ahmadis were killed and their businesses looted. The state, unfortunately, abetted the religious extremists by promulgating the notorious anti-Ahmadi laws, and arrested scores of Ahmadis nationwide for ‘crimes’ such as reciting the Kalima (Islamic Creed) or reading the Holy Quran. Among the scores arrested for their faith, three were my maternal uncles.

Therefore, I spent my formative years in a small peaceful country in West Africa. Even there, August 14 remained an important part of our lives. My mother – despite her brothers’ ordeal – played patriotic songs and related stories of our founding fathers, particularly of Mr Jinnah and Mr Zafarullah Khan. The latter is, unfortunately, a forgotten hero in the very land he fought alongside Jinnah to create. It is hard to conceive how the man who drafted the Pakistan Resolution, represented the state at the United Nations as Pakistan’s first foreign minister, and is the only Pakistani to have presided over both the UN General Assembly and the International Court of Justice, is conveniently denied any significant mention in our Pakistan studies text books.

Therefore, I spent my formative years in a small peaceful country in West Africa. Even there, August 14 remained an important part of our lives. My mother – despite her brothers’ ordeal – played patriotic songs and related stories of our founding fathers, particularly of Mr Jinnah and Mr Zafarullah Khan. The latter is, unfortunately, a forgotten hero in the very land he fought alongside Jinnah to create. It is hard to conceive how the man who drafted the Pakistan Resolution, represented the state at the United Nations as Pakistan’s first foreign minister, and is the only Pakistani to have presided over both the UN General Assembly and the International Court of Justice, is conveniently denied any significant mention in our Pakistan studies text books.While growing up, I also learned about numerous other Pakistani Ahmadi heroes, including Dr Abdus Salam, General Iftikhar Janjua, Mirza Muzaffar Ahmad, General Akhtar Malik and General Abdul Ali Malik etc. I was always proud of the role my community played in creating, stabilising and strengthening Pakistan.

Then, when I was a young teenager, we decided to return to the motherland.

Even though I knew our freedoms were severely curtailed here, Pakistan was still the only place we called home. I remember watching cricket matches with friends and family, getting heartbroken when Pakistan lost, and cheering every six that flew off Shahid Afridi’s bat. I enjoyed Pakistani television serials, fell in love with Lahore, and felt a deep sense of duty to my land of birth. Every Independence Day my elder brother and I decorated our house in Rabwah with a flag and buntings – much the same way my father would when I was a kid.

But with every passing year, the horrid state of persecution and violence increased. Extremist clerics continued to engage in vitriolic hate speech, with no public figure ready to take the risk to condemn the persecution of the Ahmadis, let alone speak for their rights. The media and public were not interested in our cause either.

Then, a series of specifically targeted attacks on Ahmadi physicians made me finally rethink my future plans, and I moved to America. Having been here for almost seven years, I still proudly identify as a Pakistani American. The word Pakistan continues to be an integral part of my identity – and it always will be.

It is August 14 again today. And as much as I am excited, I sense a strange longing deep down in my heart. When will I be able to return to Pakistan as a free citizen of the state? When will Pakistan return to the path that Jinnah set it on?

We know well that Jinnah’s struggle for Pakistan was aimed at restoring equal rights and representation, and eradicating the pain of social discrimination and economic deprivation felt by a minority – the Muslims in United India. How did it happen then that the same country that was established to protect the rights of one minority now has stringent laws denying them to another?

And despite all of this, what an exemplary display of loyalty that Pakistan’s Ahmadis consistently speak of coexistence, not separation. They continue to seek tolerance, not division. They continue to be goodwill ambassadors for the country they helped found. You might see them criticise policies that are counter to Jinnah’s vision of the country, but you won’t ever see them hating Pakistan.

Why? Because Pakistan is our mother too. And how do you hate your own mother, even when she treats you bad?

So while I am celebrating my mother’s birthday with enthusiasm as usual, true elation will be the day my mother smiles back at me. I am longing for that day. It will be the day when you, my brothers, stand up to accept me as your equal under law. It will be the day when I will be able to go back home without the fear of being arrested or attacked for reading the Holy Quran, saying my prayer or identifying as I chose to. It will be the day when the discriminatory second amendment and anti-Ahmadi laws will cease to exist, except only as a dark chapter in books of history.

Happy Birthday Mother! Pakistan Zindabad!

No comments:

Post a Comment